For All the Tenderness that Yet Remains in the World: An Interview with Poet Luisa A. Igloria

On the power of poetry, being in community, and caring for one another in tough times

Thank you to all my new subscribers - and welcome to The Village! I’m Kate – an essayist fascinated by the ways we create community in our lives, inspired by those who do it well, and convinced that thriving communities are what makes for a joyful world. I share much of my work on Instagram - join me here.

In a month where two of my own poems, “Ars Poetica” & “The Final Oyster,” are out in the world, it is such a joy to spotlight a poet whose teaching has been so inspiring and foundational to my own writing and artistic life: Dr. Luisa A. Igloria.

Igloria served as the 20th Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and is also the recipient of a prestigious Academy of American Poets Poet Laureate Fellowship to support her public poetry endeavors (which included the creation of the Virginia Poets Database here!) She has been honored with multiple accolades and awards for her work, including the Gawad Pambansang Alagad ni Balagtas lifetime achievement award from the Writers Union of the Philippines (UMPIL); the inaugural Resurgence Prize (UK), the world's first major award for eco-poetry; and she is also a Louis I. Jaffe Professor and University Professor of English and Creative Writing, and member of the core faculty of the MFA Creative Writing Program at Old Dominion University, where she was one of my beloved professors.

She has authored fourteen collections of poetry, five chapbooks, and edited three anthologies, including the prescient Dear Human at the Edge of Time. For more than fourteen years, she has written a poem each and every single day, a practice I deeply admire, even as I often hit snooze on my own alarm clock.

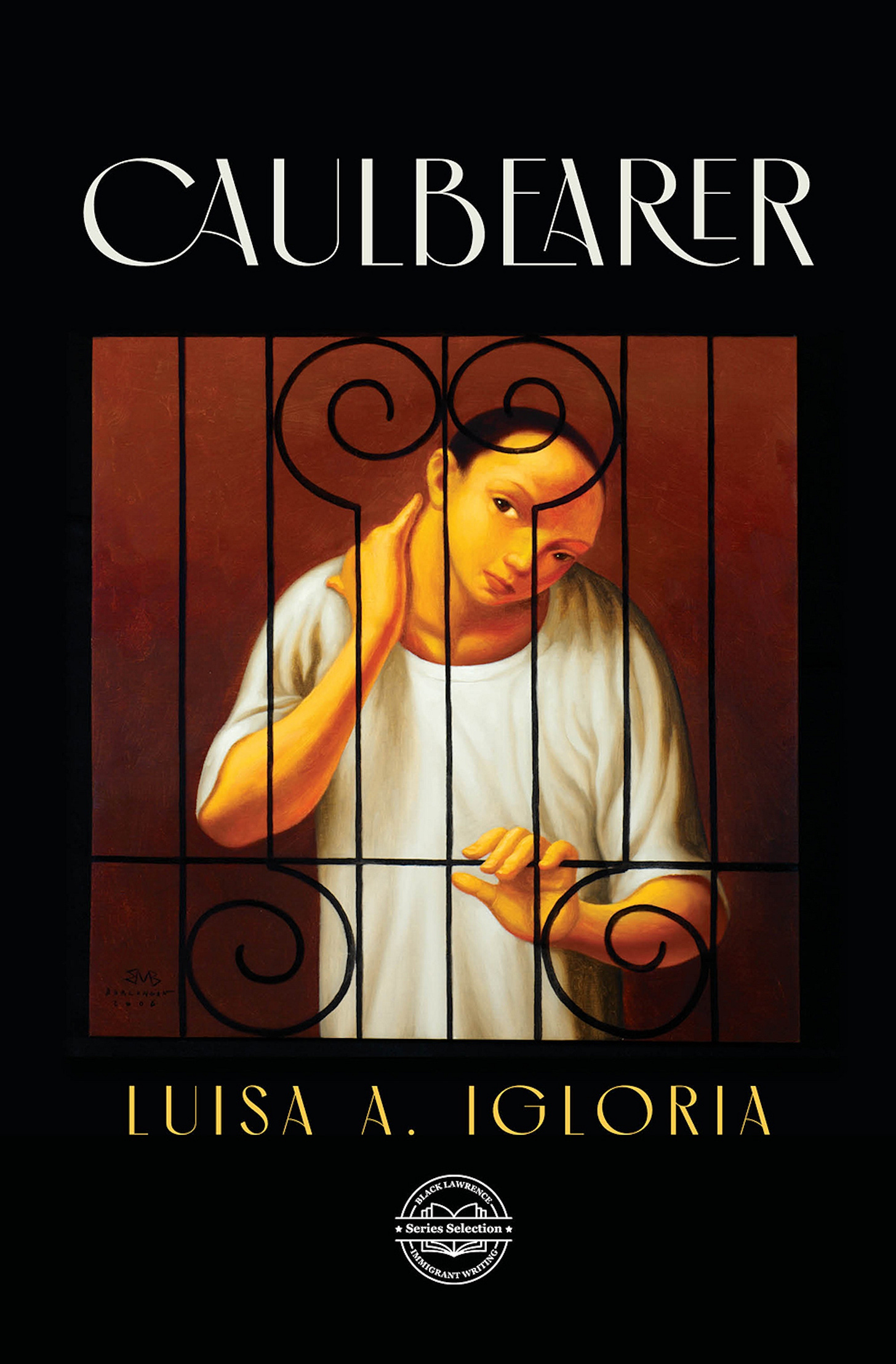

Her most recent poetry collection, Caulbearer, is out now from Black Lawrence Press and has already gone into its second printing, and next up is The Nature of Our Times, an anthology she is co-editing on ‘America’s Lands, Waters, Wildlife, and Other Natural Wonders,’ coming later this fall.

In her classes and workshops, Igloria introduced us to the zuihitsu and the ghazal, to poetry collections that challenged 'official' narratives of history, re-imagined form, and expanded ideas of beauty, encouraged clear observation of the world around us, while also imagining the world that might be possible ahead. I am so overjoyed to be in conversation with her below about Caulbearer, on joys, on legacies, and on the importance of building community. Enjoy!

KL: A ‘caulbearer’ is a term for a child born with a piece of the amniotic sac (the ‘caul’) on or over its head, and you wrote for Poetry Daily's "What Sparks Poetry" series about the cultural belief, including in the Philippines, that this is often considered an omen of good fortune, of luck, of an otherworldly glimpse beyond the veil that separates worlds. Would you share a bit about why you chose this title for your collection? What meaning does it hold for you?

LI: First of all, thank you for bringing up the essay I wrote on Caulbearer (and its title poem) for Poetry Daily. I hadn’t originally planned for this collection to move toward this title; however, putting the poems together, I kept coming back to the title poem (which also appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Oxford American). As I say in the essay, I was struck by the relationship between the yucca moth and the yucca flower: the existence they model is one of perfect mutuality and symbiosis. Considering this alongside the idea of birth (whether or not we were born with a caul), we as humans are marked forever by the first shock of emergence from the womb. Beyond the idea of the caul as a talisman or symbol of luck, fortune, or second sight, I kept returning to the idea of our vulnerability. And of how, even as we’re confronted by everything that’s hard or stony or seemingly unforgiving in life, the ability to stay present with that vulnerability can be a profound source of strength.

KL: Caulbearer draws together so many themes - loss and legacy, time and nostalgia, a reckoning with the emotional and ecological fallout of colonialism - and yet still felt so hopeful to me. One of my favorite lines comes at the start of “Poem with Two Lines from Rilke:” "There are those who carry / like a talisman such unshakeable / belief in a benevolence still at work / in the world” With so many horrific and hard things in the world, what brings you hope lately? What role does poetry play in hope?

LI: People turn to poetry because the language of poems (and art, and storytelling) is not transactional or profit-driven. It doesn’t first ask you what you can give to it in exchange for what it holds. Rather, the language of poetry has the ability to speak deeply and directly to the human in us; sometimes we feel this power even before logic or reason “explains” the experience that a poem bears. At book signings for Caulbearer of late, I’ve taken to inscribing something like “for all the tenderness that yet remains in the world.” And during these difficult times, I do feel that we’re looking to be reassured, and to reassure others, that there remains “a benevolence still at work/ in the world.” That today we can still read poems of great power and love and insight from centuries ago and feel addressed, I feel, is testament that hope and goodness exist.

KL: We’ve spoken before about one of my favorite aspects of legacy: sharing the things you love with your children and watching them learn to love those things too (or at least hoping that they will!). Famously, your daughters are also talented and accomplished poets. What led you to poetry? And how did you share your love of poetry with your children?

LI: My very first teachers were my parents, who taught me to read early (at the age of 3). They were also avid readers. Though we were not rich, they encouraged me to write and make art and music, and found opportunities to take me to all kinds of cultural experiences— the movies, concerts, ballet, theatre. And I was also fortunate to have good teachers, who continued to nurture in me the love for language and literature. When I had children, I naturally shared this love with them, while also trying to emulate what my parents had done to instruct me. All my daughters write and make art— but it’s not something I forced upon them. I was raised as the only child of parents who were twenty years apart in age, and who for a combination of reasons did not exactly think of themselves as exactly “like” other people in their circles. I think this made me, us, appreciate the pleasures of solitude. Growing up in Baguio City in the Philippines (which has a lengthy rainy season) I think also predisposed me to my own sense of interiority— which gave me the ability to explore my imagination.

KL: One other selection of my favorite lines is the stanza that closes the collection: “O outrigger. I am an island and you are / an island and everyone else is an island / and we could be an archipelago.” This felt like such a beautiful expression of the ways that we create (and to a larger human longing to create) community. What are some of the ways community shows up in your life, lately?

LI: I love this question about community, which is of great importance for everyone. I teach creative writing in the university as well as in the nonprofit Muse Writers Center in Norfolk, where I am also a member of the board. I mentor student writers and other writers who reach out to me. There is also a large Filipino American community here, with a history going back to U.S. naval recruitment in the Pacific in the late 1800s/early 1900s. Recently, at ODU, I’ve become involved in trying to coordinate with other FilAm faculty, staff, alumni, and students so we can continue to spotlight FilAm cultural programming on campus. Over a year ago now, my family and the families of two other Asian American friends decided to hold a monthly potluck in which we take turns hosting; we love and need this kind of getting together so much!

The significance of community is even more expansive for immigrants, people of color in the diaspora, and people who have experienced any kind of displacement or dispossession from an originary home. We seek out our people, those who speak our languages and share our histories, cultural legacies, and memories. Community can be found among those who speak a common language, among those who can and/or are willing to understand where we’re coming from without the over-requirements to justify who we are and why we are here. I’m grateful to find a sense of community in the intersections of what I do in my professional life— as a teacher and practicing writer— and in my personal life. While I love the sense of in-person interaction, I can’t deny that virtual connections also make it possible for us to commune with others who are elsewhere in the world.

KL: Caulbearer is already out there inspiring so many - now in its second printing! And so I would love to ask two versions of the same question I always close with - whose work inspires you lately? And also, because I know you draw so much inspiration from world around us, what have you been particularly inspired by lately?

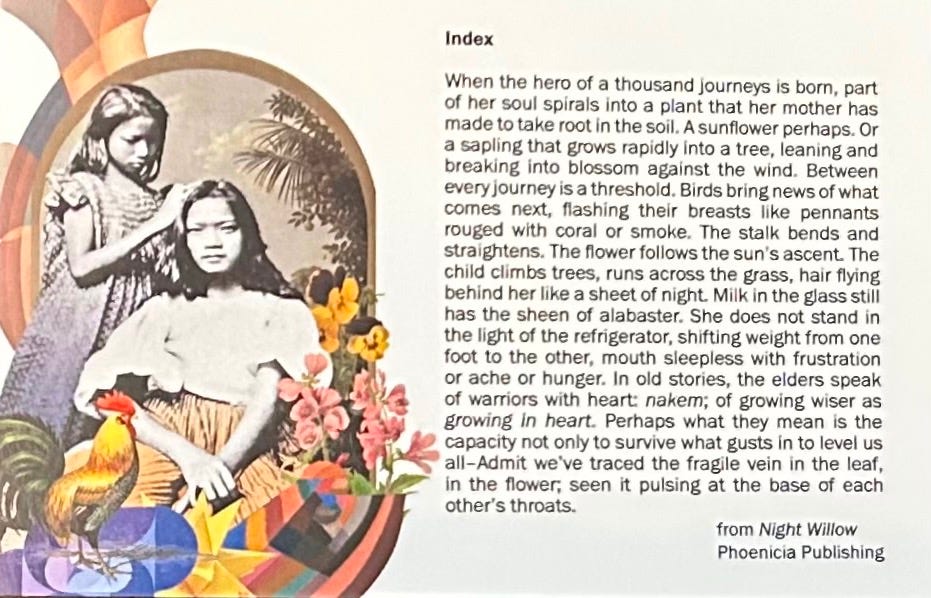

LI: The work of writers and artists of color/marginalized writers and artists inspires me so much in all the ways they seek to radicalize the idea of aesthetic practice and value. It’s through these writers and artists that I find meaningful ways to return to questions about my own relationship to tradition, and excitement at the idea of innovation. Also, because I teach creative writing and literature, this spring semester I’ve been excited to put newer and older materials together in reading lists for my students, including Han Kang (The Vegetarian), Diane Seuss (Modern Poetry), Albert Abonado (Field Guide for Accidents), Ananda Lima (Tropicalia), Paisley Rekdal (Real Toads, Imaginary Gardens: On Reading and Writing Poetry Forensically), Zoe Brossard and Erica Trabold (The Lyric Essay as Resistance), among others. I have whole stacks of to-read books by my writing desk, and hope to do better at getting through them this year. When we went into pandemic lockdown, I rediscovered the joys of collage and hand-binding (bookbinding); over the winter holiday, I also returned to old loves—pen and ink drawing and watercolor painting.

Thank you so much, Luisa, for your words and your work, and thank you to the readers! What are ways you are inspired by the world around us lately? What joys has January brought for you? I’d love to chat in the comments!

Pick up your copy of Caulbearer here, and check out my this & other recommended titles on poetry + craft at my Bookshop here.

About Kate Lewis

Kate Lewis is an essayist and poet whose work appears in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Good Housekeeping, Men’s Health, Romper, The Good Trade, Literary Mama, River Teeth’s Beautiful Things, and elsewhere. She lives outside Washington, D.C. with her husband, their two young children, and a mischief-making dog. Her work has been nominated for Best of the Net and supported by the Perry Morgan Fellowship from Old Dominion University. Find her online @katehasthoughts.

Lovely interview! I took Dr. Igloria's Asian American Literature class during my grad program at ODU and it was one of my favorite classes. She's simply amazing.